December 25, 2025

Article courtesy of Core77

Many of us can recall the pride we felt the first time we spotted a product that we had a hand in designing sitting on a store shelf. And this pride turns to absolute nirvana when that product is your product — something that you’ve brought to market completely born of your vision and manufactured by your own company.

The story I’m about to share with you chronicles my journey with Automoblox (ToyShow), a product that started out as a school project and ultimately turned into a full-time obsession. My road to nirvana was a dark and bumpy one, fraught with emotions that ranged from exhaustion and panic to frustration and rage. But the day I delivered the first order for Automoblox to a small toy store in Darien, Conn., was a day that rivals only the day that my daughter was born.

“Once we were inside, the stench of toxic fumes coming from the painting and staining rooms was difficult to stomach. Not a single person wore a protective mask. As we moved through the factory, I asked to see the shop where they formed the wood, which turned out to be a treacherous walk through construction rubble.”

The Starting Line

The high school I attended didn’t present awards for “most likely to design stuff.” Nonetheless, I was pretty good at it (for an 18-year-old) and headed to Carnegie Mellon University to study graphic design. Fortunately for me, CMU lumped together aspiring artists and aspiring designers into a basic Art School where students were exposed to art, 2D and 3D design. Like many of us, it was in a basic 3D design class where I first learned of the Industrial Design (ID) profession — a turning point for me. My future took on a new direction as I abandoned graphic design and pursued a future in ID.

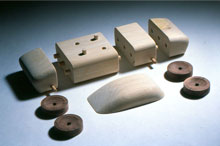

During the fall of my senior year, a local wood manufacturer came to campus, offering to sponsor a project challenging students to come up with new products for the wooden hobby market. Being a car guy, I immediately rolled up my sleeves and worked on a novel wooden car concept. Soon after, the wooden car idea evolved into a modular wooden toy system — one that inspired children to design their own cars instead of simply duplicating an image displayed on a package. I was intrigued with the idea of an interchangeable toy system that would be both fun and educational, and with one semester left until graduation, I developed the first Automoblox prototypes during that class.

Along with the design development, I spent much of my final semester in 1993 discovering that it was going to take more than a business minor to bring my vision of Automoblox to market. A cousin who had contacts in the toy industry put me in touch with a retired buyer from Toys "R" Us, who, although impressed with my wooden cars, advised me that they would need to retail for the low price of $14.99. At that price, I couldn´t see any possiblility of my making money on the project, and, stepping back from the cut-throat nature of the toy world, shelved the Automoblox idea, deciding to take a safer, more familiar road for a while.

![]()

From Andrew Carnegie to Dale Carnegie

I worked as a freelance ID guy for a couple of years and eventually landed a job at PharmaDesign, a company that makes custom promotional items for the pharmaceutical industry. Working there, I learned first-hand about rapid and efficient Far East product development. Our design process involved creating massive numbers of computer renderings that our sales force would use as tools to pitch our custom designs. To potential buyers, the renderings appeared to be actual, existing products. When we received an order, we’d jump through all the necessary hoops to actually have the product made and deliver the manufactured piece in a timely manner. This model — where only limited investment is made up front — opened my eyes to how products could be efficiently produced in the Far East.

I moved on from PharmaDesign to a position at Colgate-Palmolive, where I was baptized into the corporate world and exposed to consumer research and the power of brands. I was surrounded by some of the brightest MBAs in the world and learned to begin thinking as much like a marketer as a designer. I took advantage of the knowledge and expertise around me and always kept my entrepreneurial eyes and ears open. I had a great mentor and friend in Jay Crawford, who taught me that there’s no shortage of good ideas; the challenge is to translate the ideas to business success. That success comes from vital project and people management skills, hard work and the power of persuasion.

“At this juncture and at the height of my anxiety, I felt it was necessary for me to leave my position at Colgate; a week later I was on a plane to China.”

While I was working at Colgate, my toy idea began to take shape. During my long commute to the city, I would occupy my time reading books about visionaries like Benjamin Franklin, Abraham Lincoln, Alfred Sloan and Sam Walton. I began to spend nearly every night working on the development and business plan for Automoblox, and after four years of balancing the demands and responsibilities of my job and my family, I knew that if I was to make Automoblox really come to life, I needed to go at it full time. And so I did.

As an entrepreneur, your roles expand exponentially and change by the moment. Sure, you’re the president and CEO, but pursuing your own gig means you’re also a marketing project manager, product development manager, supply chain manager, design director, public relations manager, business development manager, director of customer service, mechanical engineer, and a lawyer, among other things. You won't have the competence needed in these areas, so you'd better have access to people who do. I have been blessed with a network of professional colleagues that were vital to this project, and my wife, Susan, can step into many roles when she’s not changing diapers and chasing our two-year-old.

A good friend, Brett Marshall, called to tell me about a book he had just finished called The Mouse Driver Chronicles. He said that while reading the book, he was constantly reminded of me and my toy car project. I immediately went out and picked up a copy. It was written by John Lusk and Kyle Harrison, two Wharton MBAs who, upon graduation in 1999, took a pass on high-paying dot-com jobs and instead decided to manufacture and market a product (a computer mouse designed to look like a golf-club head) they dreamed up during their entrepreneurship class. With some seed money from their professor and tons of their own, they set up shop and were quickly in business. Their success was modest by their own account, but they did develop an impressive following. An e-mail update to some friends turned into a Web journal that eventually became course material for entrepreneurship classes around the country, and, before long, guest lecture gigs turned into a book deal.

At the conclusion of the book, Lusk and Harrison welcomed people with new product ideas to contact them for advice. Not shy and always willing to take advantage of an intriguing offer, I promptly contacted them. At this point in the evolution of Automoblox, I was still at Colgate, and I had yet to select a supplier for the line. The three initial Automoblox products required quite a bit of tooling, which meant that a significant capital expenditure was needed to get started. Lusk and Harrison had positive experiences with their supplier, and suggested I contact the company for a quote.

Pulling My (Supply) Chain

Within a few days, I was on the phone with the Hong Kong trading company, Swift Tread. (I´ve changed the names of this supplier and its employees to protect the guilty.) Vinnie Meola was a 30-something American who had been in Hong Kong for more than 10 years getting his former employer’s sourcing business off the ground. The company eventually folded, but Vinnie stayed and started his own trading company. His partner, Lenny Chang, a Hong Kong native in his 50s who pretends to understand enough English to inspire a certain amount of confidence, is the actual liaison between the factory and the customer.

Doing business with an overseas supplier created some anxiety, but since Vinnie is an English-speaking American, I felt confident in Swift Tread. The fact that Vinnie and I are both Jersey boys further helped me to sleep at night — at least for a while. Swift Tread submitted the low bid on the tooling and per-piece price, and came highly recommended by my entrepreneurs-turned-book-writers friends. It seemed that the stars — at least in the Far East — were lining up for me and my new toy company.

"Henry was quick to to inform Mr. Ling that he did not speak Cantonese, the local language. This deception positioned Henry as a spy for me, pretending to not understand the conversations among my agent, Lenny, the molder, Mr. Ling and the tool maker. After a short while, Henry pulled me aside and advised me to get my business out of Swift Tread as swiftly as possible."

On my first trip to Hong Kong to meet my new manufacturing partners at Swift Tread, I visited the two factories they had identified to manufacture and assemble Automoblox. The plan was to have the wood factory ship the hand-made wooden parts to the plastic factory, where all the injection molding and final assembly would occur. The plastics factory Swift Tread selected was impressive. The list of customers alone sold me; they were shipping directly to all the big US retailers. They had earned Supplier of the Year from several noteworthy US manufacturers (I even took pictures of the plaques proudly displayed in their lobby), and they had in-house tooling capabilities, impressive engineering resources, a spotless factory and effective quality control processes in place. Swift Tread and I agreed on a time frame of approximately 12 weeks from the time I placed the order for tooling and the time the first container of Automoblox products would be shipped. The plan — which at first seemed safe, simple and straightforward — eventually became the cause of anxious days and sleepless nights.

Getting Ready for the Show

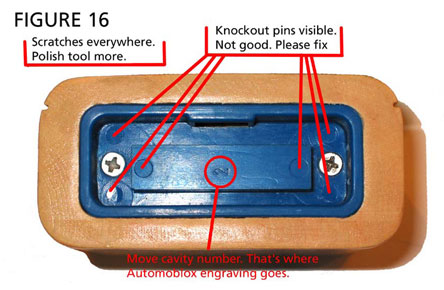

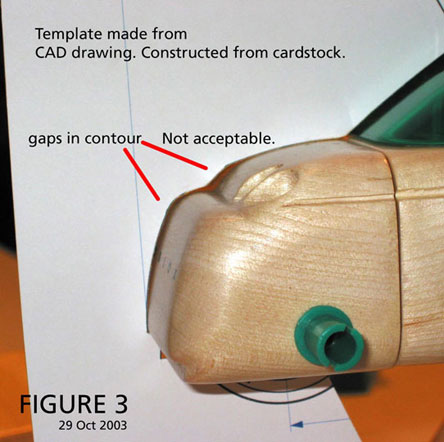

While the manufacturing work was underway, I made arrangements to showcase Automoblox at the American International Toy Fair in New York where I hoped to make industry contacts that would help launch the business. Prior to my association with Swift Tread, I had relied on Saunders Studios to craft two rounds of Automoblox models for concept evaluation and for product photography.

“My Hong Kong suppliers had painted my precision/patented connection system to match the specified colors, adding thickness to the parts and resulting in tighter tolerances of the interlocking components. In other words, they didn’t work.”

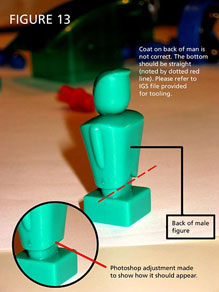

With the toy fair dates fast approaching, I decided to display appearance models, rather than actual molded parts of each of the seven Automoblox cars. I enlisted Swift Tread to do the models at a greatly reduced price compared to Saunders Studios. Swift Tread had the opportunity to examine the models that Saunders Studios had made for me — models that accurately represented the design aesthetic and the desired function. I was assured that Swift Tread would have no problem executing models of equal quality in time for the toy show. However, in a phone conversation, Lenny warned me that the models were “not too good.” I paced the floors, waiting with reluctant anticipation for the “not too good” models to arrive. My fears were confirmed when I opened the shipment to discover models that were far worse than “not too good.” They were sloppily assembled and did not function at all. My Hong Kong suppliers had painted my precision/patented connection system to match the specified colors, adding thickness to the parts and resulting in tighter tolerances of the interlocking components. In other words, they didn’t work.

With less than a week to go before the show, I had no choice but to use my original Saunders models for display purposes, and to employ the embarrassing models from Swift Tread for demonstrations. I spent the entire trade show trying to convince prospective customers that “the manufactured parts will work just fine when the final products are produced.”

![]()

I took a few small orders at that trade show in 2003, but mostly licked my wounds and gathered leads. A call from the managing editor of AutoWeek magazine would normally be a welcome and exciting opportunity for free PR, but I had to apologize for being unable to send samples. He was enthusiastic about the concept, however, and said he’d be interested in writing a future piece about Automoblox. I promised to get him samples hot off the assembly line as soon as I could. That day couldn’t come soon enough. When I finally received the first shots from the mold in September 2003 — already far behind schedule — I was feeling reasonably confident about the work, but didn’t know at the time that several more months would be spent in a futile attempt to correct the tooling needed to achieve the desired functionality.

Next Stop: Big Boys

In October 2003, I was contacted by the president of BRIO US, who expressed interest in taking on Automoblox as the sole North American distributor. Within a few weeks, we put together a distribution deal for 2004. There was also some talk of taking over the manufacturing of the line, and we discussed possible terms. But I wasn’t willing to let Automoblox out of my control at this point; I still wanted to achieve my dream of being a manufacturer.

"I began to get suspicious of the relationship between our hosts and the factory when several phone calls were placed during the drive to the factory, requesting directions. I was led to believe that they owned the factory, but they were actually brokers paid by factory owners to lure American business people to their facilities."

To my delight, BRIO issued a purchase order for 10,000 pieces! With the order came a Letter of Credit with an estimated ship date and an expiration date. (This means that if the Letter of Credit expires and Automoblox doesn’t deliver, the sale is invalidated.) This order put Swift Tread under fire to resolve the tooling issues in order to meet the delivery date for my first customer. BRIO also talked about annual forecasts in the 60,000- to 100,000-piece range. At this juncture, and at the height of my anxiety, I felt it was necessary for me to leave my position at Colgate; a week later I was on a plane to China.

During my farewell rounds at Colgate, I stopped to say goodbye to a colleague, Yvonne Hsu. Yvonne has the kind of energy that inspires commitment from her team, and she and I worked together under crazy deadlines. I shared with her my plans for Automoblox, and she expressed her support and encouragement. Although ideas for Automoblox had been playing nonstop in my mind, my friends and colleagues at Colgate (for obvious career-related reasons) were unaware of my personal project. Yvonne told me that her dad, who was in the manufacturing business, might be able to help me, and she suggested I give him a call. She warned me that I needed to be prepared to talk specifics, because Henry “isn’t the chatty type.” Her warning sufficiently scared me enough to put off calling him right away, but by February, I mustered up the courage to call for some advice.

![]()

Henry, born in Hong Kong, agreed to meet me for lunch in New York. I showed him my product, and shared with him the trouble I had been experiencing with Swift Tread. The preproduction samples functioned to some degree, but still not correctly. I told him about my upcoming trip to China to work with Swift Tread on final tool modifications and check out some new factories. To my surprise, he offered to accompany me on the trip! I explained that I was not in a position to pay him for his assistance, but he told me not to worry about it, and we agreed that I’d cover his airfare. His offer was one I could not turn down.

A Rude Awakening in China

I set off again for Hong Kong where I would meet Lenny from Swift Tread and travel to South China to review the tool modifications and to return later in the week to check on their progress. I found it more than a little odd that that impressive plastics factory I originally toured with Lenny was not on our itinerary. Instead, I ended up reviewing parts in a cramped, low-tech factory owned by the Ling brothers. In the US we call this “bait and switch,” and when I questioned Lenny on the change, he explained that this alternate factory offered better pricing. Strange, of course — my price didn’t go down.

![]()

I also planned a side trip with Henry, unbeknownst to Swift Tread, to check out some new factories in northern China. Our host for one of these visits was a young woman in her early twenties, who spoke very little English. She, along with a young man and driver — neither of whom spoke any English — met Henry and me in Ningbo to begin the trip. I began to get suspicious of the relationship between our hosts and the factory when several phone calls were placed during the drive to the factory, requesting directions. I was led to believe that they owned the factory, but they were actually brokers paid by factory owners to lure American businesspeople to their facilities. Having Henry with me was invaluable since he understood everything they said and could monitor their conversations. After three long hours crammed in a Volkswagen Passat with little to talk about, the five of us pulled up to what appeared to be a relatively impressive factory. Well, it was large, if not impressive.

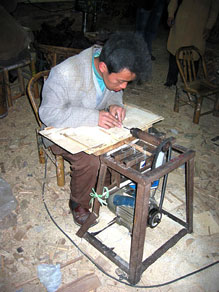

Once we were inside, the stench of toxic fumes coming from the painting and staining rooms was difficult to stomach. Not a single person wore a protective mask. As we moved through the factory, I asked to see the shop where they formed the wood, which turned out to be a treacherous walk through construction rubble. Only a portion of the shop had a roof; it had no walls. The shop tools were ancient, the lighting was dim, and the workplace was littered with scrap and garbage. I snapped a few photos because I could not believe my eyes. I told Henry to tell our hosts I’d seen enough. I wasn’t looking forward to a three-hour return trip with these people, and, to add insult to injury, was bullied into a two-hour dinner with them before we even hit the road.

The next day we were greeted by a friend of Henry’s. Jason worked for Gemmer Technology, the company that Henry had worked with for nearly 20 years. After touring Gemmer’s new, and very modern, factory we talked about my project in detail. Actually, I talked and Henry translated, since no one at Gemmer spoke English. Gemmer’s organizational structure very much appealed to me. Rather than the agent relationship, with the assortment of middlemen and “partnerships” I had experienced with Swift Tread, I would work directly with Gemmer, which houses the molder and toolmaker within their four walls. To me, this seemed less risky and meant a lower margin for error.

We traveled back to South China to review the modifications that Swift Tread had made on the current tools. My hope was they would finally achieve the desired functionality to get us through the next several months. This time, I was taking Henry back to the factory with me — two sets of eyes and ears would be better than one, especially when one set speaks the language. Mr. Ling, one of the partners from the injection molding factory, picked up Henry and me at our hotel. Henry was quick to inform Mr. Ling that he did not speak Cantonese, the local language. This deception positioned Henry as a spy for me, pretending to not understand the conversations between my agent, Lenny, the molder, Mr. Ling and the tool maker. After a short while, Henry pulled me aside and advised me to get my business out of Swift Tread as swiftly as possible. He overheard the toolmaker tell Mr. Ling that there was nothing else he could do to adjust the mold. Henry also learned that my agent, Vinnie — who was supposed to have my interests at heart — was really protecting the interests of the molder.

I took detailed photographs of the tools, gave Swift Tread the go-ahead to correct the tooling, and we left. In light of what Henry told me, it seemed doubtful Swift Tread would ever produce the parts correctly. Still, I hoped and prayed for a miracle as they went back to adjust the mold. The sad truth was that I was too far down this road with these guys, and any move to a new supplier would have to wait until 2005.

A Heartbreak With BRIO

Despite my clear specifications and a detailed evaluation of all molded samples along with detailed engineering analysis, Swift Tread never was able to achieve the standard with respect to functionality. After the disappointing trip to China in March 2004, I was forced to accept defeat; my manufacturing partners in Swift Tread weren't going to provide the quality I required.

By this time the expiration date was looming for BRIO’s Letter of Credit, and the 10,000-piece order was quickly slipping away. Because of the production delays, BRIO missed out on the spring selling season, and by their own estimation would not even be able to sell 10,000 in 2004. They were now seeking a lower price because of lost sales, and were considering other changes to the distribution strategy. I couldn’t swing a lower margin, and concluded that I would be better off financially if I managed distribution in North America myself for the first year. As a consequence, I reluctantly cut ties with BRIO.

“Despite the fact that each product embodied my global patents and trademarks, Vinnie had no qualms about breaking international laws and selling them on the open market. In this scenario, it was likely that Automoblox would be for sale somewhere in the world and I would not get one thin dime of the revenue.”

I had a new problem though. I no longer had the 10,000-piece BRIO order, but Swift Tread had already begun production of 15,000 parts — of which only 5,000 were spoken for by my international customers. Ultimately, Swift Tread was able to assemble only 13,000 pieces. I ordered an inspection by an independent company to evaluate the quality; the shipment failed inspection. A second inspection requested by Swift Tread also failed. My options were limited, to say the least. I had 13,000 products sitting in China that failed to meet my quality standards — so much for a brand strategy and four years of blood, sweat and tears. To me, releasing products that did not measure up to my own standards made me feel like I was selling out on my dream, and that was not acceptable.

Damage Control

I was in a tough situation. If I refused the goods, Vinnie from Swift Tread informed me, the factory would simply sell the goods to a broker or distributor to regain its investment. Despite the fact that each product embodied my global patents and trademarks, Vinnie had no qualms about breaking international intellectual property laws and selling them on the open market. In this scenario, it was likely that Automoblox would be for sale somewhere in the world and I would not get one thin dime of the revenue. I had to make a difficult decision. I felt a fervent need to protect the carefully crafted Automoblox brand, and decided to accept the goods at a discount. My plan was to distribute them in the United States, Japan and the United Kingdom, and to respond to consumer quality claims as they came in. By the time the dust cleared and the freight company actually delivered the goods to my warehouse, it was mid-July.

A half-page article in AutoWeek hit the newsstands in late June. Consumers were calling and e-mailing like crazy. My wife and I decided to ship all individual consumer orders directly from our office so we could actually open the cases and inspect our products before we sent them out. It was a frenzy, but many retail sales and some great wholesale accounts resulted from that article.

"To stop the bleeding. I did the only thing I knew how: I got on a plane to Hong Kong — again — to do what I was paying Lenny to do. My hope was to visit the wood factory in person to try to talk them into taking on the project at an increased cost to me."

One of those leads came from a leading men’s catalog. Based on its forecast of being able to sell 20,000 pieces, we agreed on a price. With fewer than 10,000 in stock and only four months until Christmas, I needed to get the order rolling. Because there was no time to secure a new vendor, I reluctantly put my purchase order in for 15,000 pieces with none other than Swift Tread. I knew I needed to keep afloat until 2005 and then make a quick transition from Swift Tread to Gemmer. While I was negotiating the deal with the catalog customer, I was keeping Swift Tread informed that a large order was coming and that I would likely need to increase the size of the order to 30,000 pieces. Two weeks later, I called to check on how things were going and I was informed that the wood factory was no longer interested in the job. Since I hired Swift Tread to manage production, I was having a hard time owning the wood factory problem. Swift Tread was scrambling to find a new wood vendor, but I was doubtful, given Swift Tread’s track record, that they would be able to get another wood vendor up and running in time to ship in 6 weeks.

To stop the bleeding, I did the only thing I knew how: I got on a plane to Hong Kong — again — to do what I was paying Lenny to do. My hope was to visit the wood factory in person to try to talk them into continuing on the project at an increased cost to me. The other objective of the trip was to seal the deal with Gemmer and the new wood factory, and to get them started on new tooling and production. The grueling trip called for stops in Taiwan (Gemmer’s headquarters), Japan (to visit one of my customers) and Shanghai. At this point, there was adequate margin so I could absorb a price increase in the short term, and I left the current wood factory with a deal. I agreed to pay for a new milling machine to increase its capacity if it could guarantee delivery in time for Christmas. I headed home confident in the delivery schedule.![]()

Past experience with Swift Tread told me that I also needed to change the way in which the transactions would take place. Instead of wiring half the cost of goods, as is customary, I decided to open a Letter of Credit, which would be executed upon sight of the finished goods. Swift Tread was less than receptive to this approach and began wavering on the delivery schedule in time for Christmas. Missing the holiday delivery would be catastrophic for me because the 2005 products would be made by Gemmer and would not be interchangeable with the current models. I decided to cut my losses with Swift Tread. I suspended all further sales efforts and gambled that the 20,000-piece estimate provided by the catalog company was overly ambitious, and that I wouldn't be called on to fill that kind of volume.

Susan and I survived the Christmas crush and did indeed have enough inventory to cover the catalog orders. (Sadly, I'd also had orders from other stores, distributors and individual consumers that all had to be turned down.) And despite everything — including four trips halfway around the world and a bruised ego — we lifted our glasses to toast the adventures of Automoblox’s first year.

February 1, 2005

When I look back now, what made this journey particularly difficult was having partners that were not capable of doing the job they promised. One of the most important traits in business, or in life, is being dependable, and I was given a product development and delivery schedule that was revised many times yet never met by Swift Tread. Essentially, they squandered two years of sales from me, costing me hundreds of thousands of dollars. Indeed, they could have put me out of business before I even got started. Gemmer was able to accomplish in two months what Swift Tread couldn´t do in two years. Having a reliable manufacturer is everything; with a trustworthy and dependable partner in Gemmer, I can now focus my efforts on the distribution, sales and promotion of the Automoblox brand.

So today is February 1, 2005, and here are the stats:

• I've got 30,000 pieces on order with Gemmer

• 10,000 will be going to a distributor in Japan

• 6,000 will be going to a distributor in Europe

• 14,000 will come to the United States and will be sold through specialty toy stores, catalogs and museum shops

On top of that, we have very aggressive sales goals for 2005. The tough part is figuring the wood components — the lead time on them is three months, so managing the supply chain requires an investment of capital, some major-league time planning and a little bit of luck. Gemmer says that if the wood is ready, they can crank out 50,000 cars per month. We're hoping to max 'em out.

And the story that I've shared with you is really only one part of the Automoblox epic, focusing on the supply chain and all the pitfalls that await any entrepreneur. There are also tales of design, engineering, identity, marketing, intellectual property and the rest of the kitchen sink. And all this didn't happen in a vacuum, of course. During the time of this story, I got married, had a baby, broke up with a would-be business partner and endured several lawsuits. Life didn't stop for this project, and it never will. Now that things are on track, I'm hoping to spend more time coming up with great products for people all over the world to enjoy.

So if you see Automoblox on a shelf one day, you'll know what sweat and tears went into it. There were lessons about business relationships and international commerce — and, yes, a case study for next semester's entrepreneurship class — but there is the satisfaction of bringing something into the world that didn´t exist before. Stay tuned.

|

|

||||

| Copyright © 2005 Core77. All rights reserved | ||||

Copyright © 2025 TDmonthly®, a division of TOYDIRECTORY.com®,

Inc.